Simon Bolivar is often described as the Liberator. He was a major and imposing figure in the history of South America, leading the continent through a tumultuous era of revolution and independence from Spanish colonial rule. He was born on July 24, 1783, in Caracas, Venezuela. Bolivar was the scion of a wealthy Creole family and received a privileged upbringing. However, his life would take a dramatic turn, fuelling his lifelong dedication to the cause of liberation.

Bolivar’s political awakening came in his early twenties when he witnessed the brutal repression by Spanish authorities against those advocating for independence in South America. Inspired by Enlightenment ideals and the successful independence revolution in North America and the revolution in France, he resolved to dedicate his life to the emancipation of his homeland and the broader South American continent from Spanish domination. His journey towards leadership began in 1810 when he joined the Venezuelan independence movement. He very quickly rose through the ranks, demonstrating exceptional military prowess and strategic acumen. His first major victory was in 1813 when he liberated Caracas, declaring Venezuela’s independence. However, his triumph was short-lived as internal divisions and Spanish counterattacks forced him into exile.

Nonetheless, Bolivar embarked on a remarkable campaign across the Andes, rallying support and leading insurgent forces against Spanish armies. In 1819, he achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Boyacá, securing the independence of present-day Colombia. Bolivar’s military genius and charisma earned him the admiration of his followers, who affectionately referred to him as the George Washington of South America.

Bolivar’s vision extended beyond the borders of his homeland. Remarkably, he dreamed of a united South America, free from colonial shackles. In pursuit of this grand ambition, he waged campaigns across present-day Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, securing their liberation from Spanish rule. His efforts culminated in the creation of Gran Colombia, a vast republic encompassing much of northern South America. In spite his military successes, Bolivar faced formidable challenges in governing the newly liberated territories. Internal divisions, regional rivalries, and the spectre of foreign intervention threatened to unravel his dream of continental unity. He faced mounting opposition and disillusionment. Bolivar reluctantly resigned as president of Gran Colombia in 1830, disillusioned but undaunted in his commitment to the cause of liberty.

Simon Bolivar’s legacy transcends his military exploits. He was a visionary statesman who championed the principles of democracy, equality, and social justice. His efforts paved the way for the independence of numerous Latin American nations and inspired future generations of leaders in their quest for self-determination. He continues to be revered as a national hero across much of South America. His name is synonymous with the struggle for freedom and independence. Statues, monuments, and institutions bear testament to his enduring legacy.

This is the Bolivar of historical reality. Garcia Marquez’s Bolivar transcends the merely legendary. His account exploits language, that repository of the mythopoetic, to give Bolivar mythical status. As Marquez himself says, at the outset of writing his account of Bolivar he was not ‘troubled by the question of historical accuracy’. He took as his starting point, Bolivar’s last journey along the Magdalena River, the least documented period of Bolivar’s life. We are lucky that Marquez’s choice was to inhabit the poetic rather than the tedium of the strictly factual. The method combines the quicksand of delirium, the unbounded limits of the dreamworld, the untrustworthy territory of memory and that most unsurpassable faculty of all, that of storytelling.

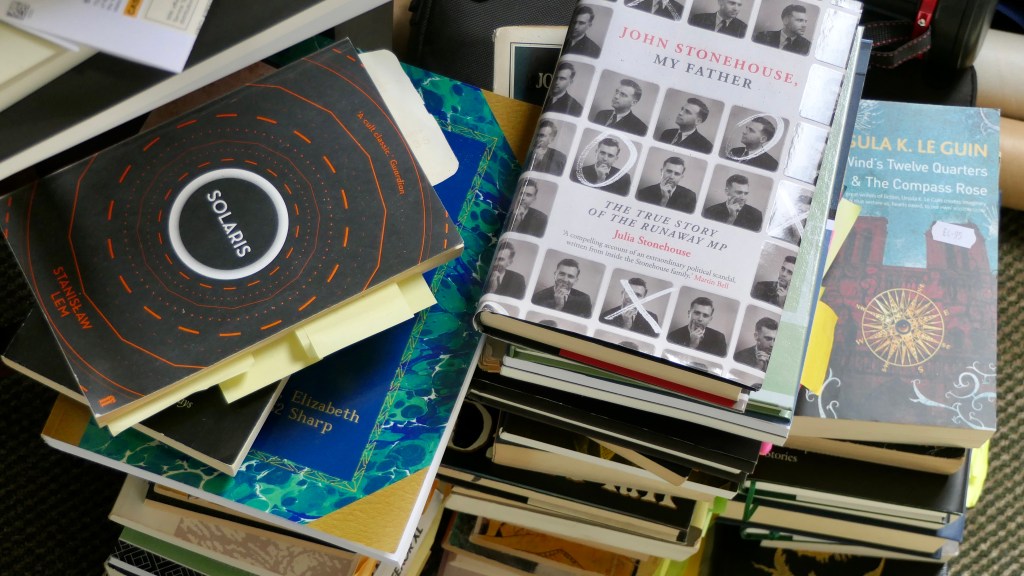

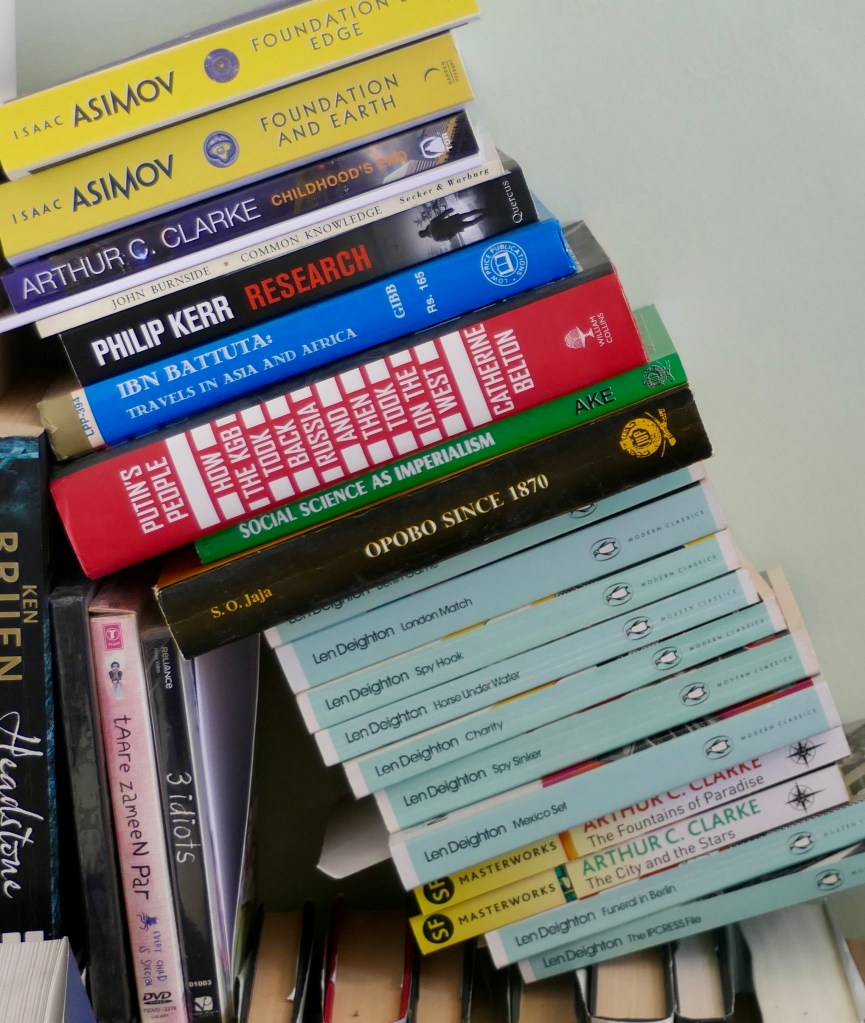

But why am I drawn to Bolivar? It was to do with discovering Bolivar’s perilous disease, his addiction to books and reading. As Marquez says, ‘he had been a reader of imperturbable voracity during the respites after battles and the rests after love, but a reader without order or method’. He read everything that came his way and like me, did not exactly have a favourite author but rather many who had been his favourites at different times. The bookcases in his houses were always crammed full and the books spilled over into bedrooms and hallways. And he never read all the books that he owned. Here was a picture of a soldier, a statesman, a man of action who was also contemplative, a man whose inner life was replenished and nourished by the thoughts of others.

When he had won the independence, one of his comrades asked him “We have independence, General, so now tell us what to do with it?” Bolivar replied “Independence was a simple question of winning war, the great sacrifices must come afterwards, to make a single nation out of all these countries”. You can argue that what Bolivar had seen in early 18th century is still true today in Africa; Independence is the easy bit, ruling fairly and true liberation are harder still, perhaps nigh impossible.

In this last journey along the Magdalena River, Bolivar was terminally ill. Yet, his energy and indefatigable will were transparent despite the frailty and weakness of his body. Marquez says that his bones were visible under his skin, there was a hot stench to his breath, the stench of impending death and he had shrunk in size and weighed 85 pounds. Yet, the vigour of his sexual life before, in his prime, and when he was close to death raised that imponderable question of the relationship between a grand purpose, an acquisitive trait, pure dynamism and sexual ardour. His eternal love, Manuela Sáenz was an astute, indomitable, graceful woman of unbounded tenacity. She followed him everywhere with her caravan of mules, slave women, six dogs, three monkeys, a bear, cages of parrots and macaws. Then there was Camille, a French woman born in Trois-Îslets where Napoleon’s Josephine was also born. She was beautiful and dazzling but publicly travelled with someone else so that her relationship with Bolivar was clandestine and shrouded or clouded, depending on your choice of words. Towards the end, Bolivar saw a young girl and she was brought to his bedroom: she ‘was languid and mysterious’ and was intelligent. She was invited to lie down with him and in the morning he said “You’re leaving a virgin” and she replied “No one is a virgin after a night with your excellency”. As for Delfina Guardiola, when she became enraged by his inconsistency and shut the door of her house against him, he climbed through the kitchen window and spent three days with her.

Bolivar had Manuel Piar executed. Piar was black and had earned as much glory as anyone else. Piar had called on black people and the destitute to resist the white aristocracy of Caracas, symbolised by the General. He was executed on October 16th despite requests and entreaties that Bolivar commute the sentence. Bolivar refused to witness the execution and was heard to sob as Piar was shot. Bolivar later said, ‘Yesterday was a day of sorrow for me”. For the rest of his life Bolivar would say that it was a political necessity. This was a case of using the execution of a close comrade as an example to others much as Hitler did with Ernst Röhm.

Bolivar, himself had a bit of Africa in him such that the aristocrats in Lima called him Sambo. But who was he? He was born at San Mateo Plantation to a wealthy family. His father died when he was 3 years old and his mother when he was 9. His wife died when he was 20 years old, 8 months after their wedding. And he never spoke of his wife. As Marquez put it, ‘he had buried her at the bottom of a watertight oblivion as a means of living without her’. He recalled her once, close his death, when he suddenly remarked “Her name was Maria Teresa Rodriguez del Toro y Alayza” and he continued “The woman who was my wife. But forget it please: it was a misfortune of my youth”. Tragedy gave birth to his transition into politics and mythology.

At his death, Fernanda Barriga attempted to enter the bedroom where he lay dying saying “This poor orphan liked women so much, he can’t die without one at his bedside, even if she’s as old and ugly and useless as I am”. Even though they refused her entry, she sat outside praying for him as he raved as a pagan would. After his death she lived in eternal mourning and died at the age of 101 years.

Photos by Jan Oyebode

Prof, I have read Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred years of solitude and now with this post, I have to read his other works! Thanks for whetting our appetite!

PS. If there’s a “reader-in-residence” post at your personal library soon, sir I as am sure many others would really love the experience!

Ayomipo,

Thanks for your comments. Marquez is/was an extraordinary writer and I am sure you’ll love his other works.

Femi