Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin is a powerful and bleak novel set in Nazi Germany during World War II. It is based on a real Gestapo case file, and explores individual resistance in a totalitarian regime, focusing on the quiet rebellion of an ordinary couple, Otto and Anna Quangel, in Berlin. The story begins in 1940 with the news that the Quangels’ only son, a soldier in the Wehrmacht, has been killed in action. This personal tragedy becomes a turning point, especially for Otto, usually an introverted and dutiful factory foreman. The death of their son awakens Otto’s sensibility and moral awareness such that he starts to feel betrayed and horrified by the regime’s brutality. He decides to resist the Nazis in the only way he can conceive of, by writing and secretly distributing handwritten postcards with anti-Hitler messages, which he leaves in stairwells and public buildings around Berlin.

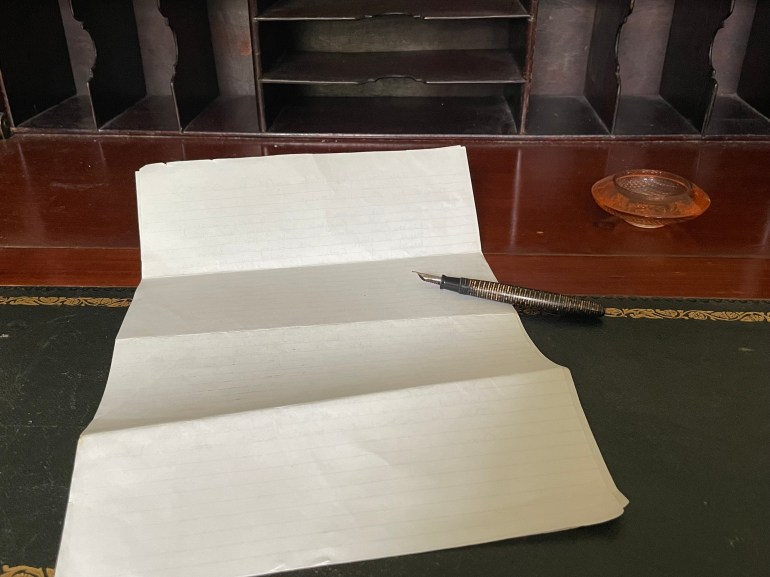

This is the central theme of the book, an exploration of small acts of resistance, that somehow purifies the spirit, even if, in the end it is unsuccessful. Anna, initially more fearful, soon joins Otto in this quiet revolt. Over the next two years, they distribute dozens of postcards, risking their lives to voice their dissent. Most of the cards are quickly handed in to the Gestapo by fearful or opportunistic citizens, but the Quangels’ persistence creates a ripple of paranoia and an elaborate investigation within the regime.

The narrative follows not only the Quangels but also a range of Berliners, illustrating how different people respond to life under Nazi rule. Among them are Emil Borkhausen, a petty criminal and informant; Judge Fromm, an honourable man quietly resisting in his own way; and Inspector Escherich, a weary Gestapo officer assigned to find the mysterious “Hobgoblin” who writes the postcards. Over time, Escherich becomes both obsessed with the case and quietly sympathetic to his targets. However, he too is trapped in a system that demands absolute loyalty. It is in Escherich and Borkhausen, that we come to see how Nazism walks hand in hand with corruption, both moral and financial, and how the corruption becomes the vehicle that drives the population to become complicit and active participants.

Eventually, Otto and Anna are betrayed and arrested. Their trial is swift and their sentence certain: death. Yet, even in captivity, they remain calm and dignified, having regained a sense of personal agency and moral clarity through their actions. In prison, they maintain a quiet strength and do not repent their rebellion. Otto is executed. Anna dies in an Allied air raid, before her sentence is carried out. Despite their deaths, the novel suggests that their small acts of defiance carry profound moral weight.

Alone in Berlin paints a grim portrait of Nazi Germany—a world of fear, suspicion, and moral compromise—but also honours the quiet courage of ordinary people. Fallada’s depiction of resistance is deliberately unsentimental; the Quangels’ postcards achieve no political change and inspire no uprising. Yet their resistance is meaningful, in itself, a refusal to participate in evil and a reclamation of dignity in the face of dehumanizing power.

Fallada’s work is relevant in today’s world, as we are thrown headlong into the possibility, if not probability, of fascism. The centre of power, of Western power, has become compromised such that we might as well say that the sewers are open, and the scent of ordure like a miasma, is floating and permeating everything. And the question can be asked, once again, what can one do, what act of resistance is necessary and how can we protect ourselves from the moral decay that is obvious and present?

In Fallada’s work, the centre of power is distant and remote from the theatre of action of the novel. Nonetheless, the effects of the centre’s actions are inescapable. Whilst there is no direct exploration or interrogation of the nature of central power, we experience it to be immoral. But, in our time, the nature and narrative of the centre of power is there to see. It is overtly cruel, openly corrupt, and also inept but effective in its use of terror and brutal force. One could argue too, that there is a degree of madness at the very heart of power.

The Yoruba talk of sínwín, and the English of crazy, and German of wahnsinnig or verrückt. The materiality of these words in the mouth, the force or effortfulness in pronouncing them hint at the friction of the abnormal as it rubs along the normal, a kind of grating or travelling against the grain. So, I am not, here, referring to a clinical state but to a profound dislocation in being, in being with others, in acting outside the boundaries that mark us all as members of the kingdom of ends, as Kant might have put it.

It is Luigi Pirandello’s Henry IV that best captures the subversion of normality in the centre of Western power, for it is in the end an allegory of the performative aspects of power, the theatricality of power. In this past 3 months, we have been subjected to, a play, a poorly scripted and poorly acted play, but nonetheless, one that has influence and power outside of its immediate environ. Pirandello’s Henry IV is a thought-provoking and darkly comic play that explores themes of identity, madness, and the thin boundary between illusion and reality. A hallmark of Pirandello’s modernist theatre, the play interrogates the nature of selfhood and performance, posing deep philosophical questions about the roles we play and the masks we wear.

The central character is a man known only as Henry IV, an Italian nobleman who, years earlier during a masquerade on horseback, fell from his horse and suffered a head injury. At the time of the fall, he had been dressed as the medieval Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, and when he awoke, he believed himself to be the real emperor. For the past twenty years, his wealthy family and household have indulged this delusion, maintaining an elaborate recreation of an 11th-century court at his estate, complete with courtiers dressed in period costume. This enactment mimics, the Great Leader’s cabinet meeting that was filmed on 11 April 2025, showing grown men and a few women who held offices of state, bowing and scraping and touching their forelocks in the presence of the Great Leader. Much as in Pirandello’s play.

As the play begins, we learn that Henry’s condition may not be as straightforward as it seems. A group of visitors has come to see him, including Donna Matilda Spina, a former lover; her daughter Frida; Matilda’s lover Baron Tito Belcredi; and Dr. Dionisio Genoni, a psychiatrist who hopes to cure Henry. They plan to shock him back to reality by confronting him with a tableau from his past—Frida dressed in the same costume Matilda wore on the day of his accident. In our time, there have been varying visitors, leaders of other countries who in the style of ancient Persia, attend as satraps, provincial and subordinate governors, who attend to show fealty to the Great Leader, only to discover that the Great Leader is naked and mad. This realisation is disguised but plain to see as a rearrangement of the structures of power in the West emerges.

Henry IV is ultimately a play about the instability of identity and the tragic consequences of attempting to live outside the roles society assigns. It speaks to the consequences of portraying oneself as an emperor despite being a democratically elected leader. Pirandello uses metatheatre and layered performance to explore how people become imprisoned by the very fictions they create much like the Great Leader, who does not realise that he is now imprisoned in a theatre of his own making. Henry IV blurs the line between sanity and delusion, between illusion and reality, revealing how reality itself can be just another carefully maintained mask.

In Fallada’s Alone in Berlin, the end is grim, that world has to collapse in its entirety through defeat at war, for there to be release for everyone else, for there to be freedom from the tyranny of the centre. There is a possibility of a different outcome in our time. The Regency Act of 1811 was required to rid Parliament of the Madness of George III. Some sort of legislative act may be required to rid us of the perfidy of the Great Leader.

Photos by Jan Oyebode