George Seferis was born Giorgos Seferiadis on March 13, 1900, in Smyrna (now Izmir, Turkey). He is regarded as one of Greece’s most celebrated poets and a Nobel Prize laureate. His work is characterized by its deep connection to Greek history and mythology, its modernist aesthetic, and its exploration of themes such as exile, memory, and the human condition.

I was drawn to Seferis’ work, as a young poet, because of the way that it was influenced by Classical Greek mythology, not as an exhibition of a classical education or great learning but organically, as a person whose spirit was infused with myth and whose writing embodied and transmitted the essence of mythical thinking, effortlessly. For a Yoruba poet, embedded in a rich tradition of myth and mythmaking, and who inhabited the world of the living and dead, and the world of the unseen and transitional spaces, Seferis was a great example of how to profit from this gift.

Smyrna, at the time of Seferis’ birth was a bustling, cosmopolitan port city known for its diverse population and vibrant cultural life. Situated on the Aegean coast, Smyrna was one of the most important cities of the Ottoman Empire, serving as a major centre for trade and commerce. Its population was made up of Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Jews, and Europeans. There was religious diversity too, as the city was home to various religious groups, including Greek Orthodox Christians, Muslims, Armenian Apostolic Christians, Jews, and Roman Catholics. This religious plurality contributed to the city’s rich cultural tapestry and diverse social life.

Seferis’ early years were marked by displacement. After the Greco-Turkish War and the subsequent population exchange between Greece and Turkey, his family relocated to Athens. This experience of exile profoundly influenced his poetry, accenting it with a sense of loss and longing. Seferis studied law in Paris, which brought him into contact with contemporary European literary movements in early 20th century.

It is to his preoccupation with exile that I turn. In Seferis, exile is as much exile from the past, the historical past as it is exile from the mythical past. There is always too, exile from his place of birth, an exact place and time, much as I might feel as an exile from a Lagos of the imagination. The sense of exile, in Seferis, often took the form of nostalgia:

The house when you examine its old cornices closely,

wakens with a mother’s footsteps on the stairs

the hand that arranges the covers or fixes the mosquito net

the lips that put out the candle’s flame.

This is exile as a longing and yearning for home, as nostalgia. The word “nostalgia” was coined in the late 17th century by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer. He used it in his medical dissertation in 1688 to describe the severe homesickness experienced by Swiss mercenaries who were serving far from their homeland. Hofer combined the Greek words “nostos” and “algos” to create “nostalgia,” intending to describe the psychological and emotional pain associated with longing for one’s homeland.

In “Return of the Exile” Seferis writes

“My old friend, what are you looking for?

After years abroad you’ve come back

with images you’ve nourished

under foreign skies

far from your own country.”

“I’m looking for my old garden;

the trees come to my waist

and the hills resemble terraces

yet as a child

I used to play on the grass

Under great shadows

And I would run for hours

breathless over the slopes.”

In Seferis, aspects of the past are painful to revisit, yet they must be revisited, since writing involves deep dives into autobiographical memory and examination and exploration of what it means to live, given what we have experienced.

In “Last Stop”, Seferis writes:

And if I talk to you in fables and parables

it’s because it’s more gentle for you that way; and horror

really can’t be talked about because it’s alive,

because it’s mute and goes on growing:

memory-wounding pain

drips by day drips in sleep.

And war is not too far from Seferis’ concern. He writes in “Salamis in Cyprus”:

“Lord, help us to keep in mind

the causes of this slaughter:

greed, dishonesty, selfishness,

the desiccation of love;

Lord, help us to root these out…”

To which I answer “Amen”.

Seferis’s first collection, Strophe (1931), signalled his arrival on the literary scene. The poems in Strophe reflected his engagement with Symbolism and early Modernism, blending classical allusions with personal introspection. His language was precise and evocative, often employing imagery drawn from the Greek landscape and history. The 1930s were a period of intense creativity for Seferis.

His second major work, The Cistern (1932), continued to explore themes of memory and the passage of time. However, it was Mythistorema (1935) that solidified his reputation as a leading voice in Greek literature. This collection consists of 24 poems that intertwine personal experiences with broader historical and mythological themes. The fragmented, almost stream-of-consciousness style of Mythistorema reflects the influence of T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, while its content is deeply rooted in the Greek tradition.

Seferis’ work often grappled with the idea of Hellenism, not as a static cultural heritage but as a living, evolving identity. His poems frequently evoke ancient myths to comment on contemporary issues, creating a dialogue between the past and the present. This is evident in his collection Gymnopaedia (1936), where he employed the Spartan ritual of the same name to explore themes of loss and renewal.

During World War II, Seferis served in the Greek diplomatic corps, an experience that exposed him to the ravages of war and exile. This period inspired some of his most poignant work, including the collection Logbook I (1940). His diplomatic career took him to various countries, including South Africa, the Middle East, and the United Kingdom, further enriching his poetic perspective. Seferis’ later works, such as Logbook II (1944) and Logbook III (1955), continued to reflect his themes of exile and displacement. In these collections, the poet’s voice becomes more introspective and contemplative, often tinged with a sense of resignation and melancholy. His 1963 collection, Thrush, is particularly notable for its meditation on aging and mortality.

In 1963, Seferis was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, recognized for his “eminent lyrical writing, inspired by a deep feeling for the Hellenic world of culture.” This accolade not only acknowledged his contributions to Greek literature but also underscored the universal resonance of his themes. Seferis’ prose works, including essays and diaries, are also significant. His essays on poetry and literature reveal his deep engagement with both Greek and international literary traditions. His travel diaries, such as Days (published posthumously in various volumes), offer insight into his personal reflections and creative process.

George Seferis passed away on September 20, 1971, in Athens, but his legacy endures. As he wrote:

[…]

so words

retain a man’s imprint

after the man has gone, is no longer there.

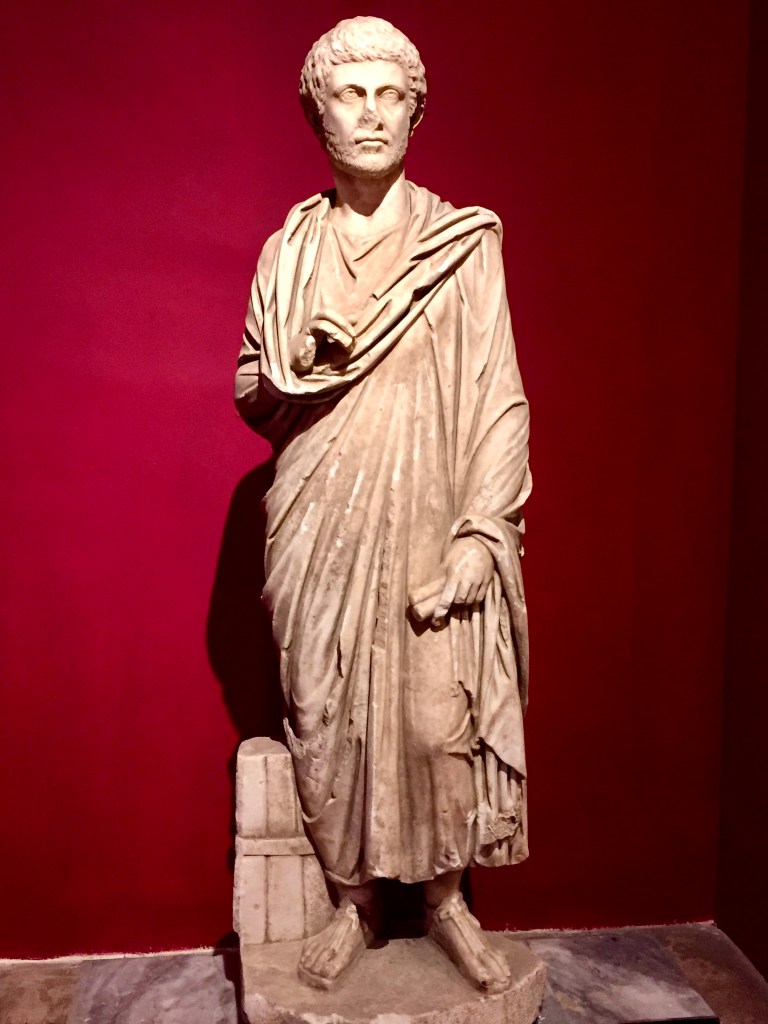

Photos by Jan Oyebode

so words

retain a man’s imprint

after the man has gone, is no longer there.

Truly.

In Sanskrit, and in Malayalam (my South Indian mother tongue), akshara (English: word) literally translates into a – not and kshara – perish, that which does not perish.

A word is that which does not perish.

I am a higher speciality trainee in Psychiatry in the UK (West Midlands) and I have been fortunate enough to listen to your talks Prof. Oyebode.

Thank you Amal. I will remember akshara. What a wonderful term for ‘word’. Femi